Climbing to Freedom with Bernadette McDonald

by katiclops

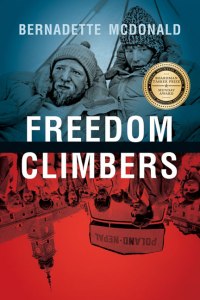

As Hurricane Sandy sweeps the east coast and earthquakes rattle the west, I felt like this might the week to review Freedom Climbers, by Bernadette McDonald. It’s been nearly two months since I tore through this novel. I felt intimidated at first…It was amazing, captivating and gripping.

It has taken me awhile to collect my thoughts about the book simply because it was so good. Partially, this can obviously be attributed to the journalistic prowess of Ms. McDonald, surely too, the editorial staff had something to do with it’s success. The final product is a pleasing size, red and blue jacket and blindingly white paper (it’s only when you are reading off of truly snow-white paper when you realize how rarely you complete such a task). But ultimately, this book is great because of the story. Non-fiction, written by a Canadian, it is the story of these climbers that made me weep (I am by no means a cryer). It also prompted me to climb a (little) mountain.

For my birthday we rented a car for the day and drove up the Sea to Sky highway to Whistler. I hadn’t been up there since 2008, and then only twice: once in the torrential rain with a highway engineer and his family; and once in the dark, playing loud alt-rock from the nineties and singing along at the tops of our lungs on a spontaneous midnight road-trip to Skookumchuck hot springs in Lillooet. This trip was in the light, in the dry, on the wide, flat, new divided highway. We had miraculously been upgraded to a new VW Beetle (thank you hotwire) and I felt as though we had won the lottery.

Generally speaking I do not drive cars with any kind of engine pick-up or brakes (my first and only car, Thomas, warrants a much longer tribute in a future blog post), so driving a brand new Beetle, with all of these things on a crazy highway was icing on the cake. We bought burritos and hiked them up to the top, eating them in brilliant sun before heading to steam and sauna and nap for the afternoon. I finished the book there, in the mountains by the fire on my birthday. The summit of the Chief fresh in my mind and ache on my body. Liberation.

Vancouver, September, 2012

In Newfoundland we climbed some mountains. They are the first ones I ever remember climbing right to the very top. The first ones I ever remember getting that little summit-high. My co-worker, my supervisor and I were always the three who would stick it out right to the end, the three locals preferring to relax on grassy knolls at the bottom, and the Torontonian stranded with the weak ankle.

My supervisor was a Newf and might as well have been half mountain goat. She’d leap and scramble ahead without a second thought. My co-worker, an Ottawatonian, was tall and lanky, moving deftly and assuredly along with all the grace of an orangutang swinging through tree tops. He was slower though, he had to stop regularly and reflect aloud, commenting on the silence, the scenery. He had a sister, and at times I suspected he lagged behind instinctively because of me. I would lumber along, head down, so engrossed with moving my heavy stout frame and red MEC pack precariously up the cliff that I would forget to look up. Often I wouldn’t even realize until I was almost be on top of him, stopped dead in his tracks. He would be staring off into the horizon, pondering aloud, or eagerly with his camera outstretched: “Do you mind taking another one? Right here would be great.”

He was obsessed with this idea that his parents would have no good pictures of him if he went missing or died, and we were endlessly taking solo shots of him part way up the mountains, on top of the mountains or against the stark salty Atlantic vistas. He told me a few years later, when we met at a food court in Ottawa one frigid, snowy winter that he really regretted that – that he should’ve taken more pictures of all of us, of what was actually happening. That when he was going through all his pictures at home they looked a bit ridiculous, this shoebox filled with all these shots of him against empty landscape. That it wasn’t the place, but the moment.

Not that you can really capture that on film anyway.

The Newfoundland mountain tops also provided us with the rare instances of cellphone reception, where he would always call his father and she would always text her boyfriend. Cell-phoneless until 2007, I would just stare out in the direction of Europe and attempt to conjure up some sense of genetic, ancestral longing. Occasionally I would look west, in the direction of home. He would always speak to his father in Persian, and each time we reached the peak he would tell him that: “his space was empty.” I thought it was one of the most beautiful thoughts you could have about someone, that of their absence but also their place. Sometimes as he would say this I would mentally import my people around me, perching them on rocky bits of the peak and for a moment their presence would be there with me, briefly, on top of the world.

This is why they climb. For the open space. For the silence. For the moment of elation and freedom the second you arrive at the top. For the release from your feet, from staring at terrain and rock faces for hours, for days for weeks. For the moment where you finally look up, look out, look across at the horizon of other peaks. The moment you are free to stop thinking that you are going to the top. For that moment when you finally get there. The release from the trees and the faces…Only to look out, across, at the ocean of peaks, at the ocean of other trials, potentials, of needing to know what it looks like from over there. From that one.

It’s easy to see how people get addicted to this stuff.

“At that moment I felt I had the gift of infinite time…I felt no triumph, but I did feel that God was near me…”

-Wanda Rutkiewicz, on her thoughts of summiting K2

A few years later across the Atlantic at Arthur’s seat

Edinburgh, Scotland – January, 2007

The premise of Freedom Climbers is great, probably not one many people know. During Communism, Poland was bound by the forces that were, restricted from traveling and repressed by the system. What happened? Climbing. A small group of people began getting really, really into mountain climbing. First the Tatras, then on to the Himalayas. Poland’s currency was massively undervalued in the 70s and 80s: as a result few imported items were available in the country. Ice axes had to literally be forged at a blacksmiths shop, “just short of plucking the geese [themselves]” mountaineering jackets assembled and sewn by hand.

Climbers on the Katowice smokestacks.

Photo credit: Krzysztof Wielicki borrowed from this blog.

After an act passed permitting social clubs to receive payment and funding, a new development occurred that greatly facilitated expeditions. Climbers would approach many of the factory owners regarding their high chimneys (which needed to be kept in good paint and fine repair). Normally, re-painting the stacks was an expensive, labourous and convoluted task, involving several weeks, permits, installation of scaffolding, etc. Climbers would approach the owners and offer to repaint in a matter of days, quickly, using their ropes and no scaffolding. Many owners agreed – even for a heady profit that was paid to the climbing club, the owners recouped a large savings. Climbing clubs were quickly financed and helped facilitate more interest and more revenue.

Overland transportation to Nepal, from Freedom Climbers

Other strategies included recruiting foreign climbers (and foreign funds) to be part of Polish climbing expeditions, as well as Polish climbers working ingeniously to maximize the value of the zloty. One way would be to purchase as much as was undervalued within Poland (i.e., food), and then travel overland to Kathmandu where they would resell as much as they could and swap with international climbers for missing items. Polish climbers would also scrounge the mountainside and abandoned base camps for tents and other lost gear that could be salvaged, reclaimed and repaired.

Polish climbers were special. They were tough, tenacious and supremely focused on their goals. They were geniuses. They knew how to live with uncertainty. They manipulated an impossible system so well that they were able to realize their dreams. They travelled, saw the world and lived lives of adventure and intensity. They had the perseverance of pioneers and the values of patriots.

You can tell Bernadette McDonald is a climber, that she lives amongst the mountains. The book is dense with research and lots of focus on the technical aspects of climbs. McDonald’s simple, barebones style, is a bit like offering stage directions to a screen play. It is has such a phenomenal pretense, the characters have such chemistry, such lofty ambitions, the political climate almost unfathomable to a North American…the writing doesn’t need to be amazing, because the story is simple and incredible and rich with emotion. The simple style that she offers the story does not detract, but rather strengthens it’s richness. The fact that the writing does not detract from what is going on in the book is a testament to it’s virtue. It is well tailored clothing over an incredible body, invisible Emperor’s Clothes, allowing us to feel as though the story is springing up out of history. Resting lightly on literary and historical quotes – a perfectly matched seam, an immaculately pressed crease.

The use of pictures throughout the book is part of the captivation: these were real people. These were real people who were climbing while I was alive, while my aunt was there. Looking through the pictures I was overcome with the breathless tangibility of living breathing history, they way you feel when you are in Berlin, drinking by the wall or standing at Checkpoint Charlie. The recent truth is screaming from the ugly, contemporary architecture in an ancient city. History alive. And not just everyday history, but something immense that has just happened. This book was filled with the kind of palpable history that is pulsing through Berlin, the echoes that scream at you from living, abandoned buildings, the way – just for a second – time slows down as something monumental is taking place. These people are my parents age. That’s the year I went to preschool. This was just happening. Looking through the photos that span twenty-five years of the book the reality becomes all the more immediate.

These are people.

They are aging.

They are living – they are the highest humans in the world.

And they have died.

“We should not presume to judge those who seek out danger on the world’s highest places or demand to be told the meaning of what they do..Simply, when they pay the ultimate price for their passion, we should remember them.”

-Wanda Rutkiewicz

This book is a testament to their memory.

Andrzej Czok and Jerzy Kukuczka on Dhaulagiri

Photo credit: Adam Bilczewski from Freedom Climbers

– Day 1 –

[…] Climbers (written by Bernadette McDonald and initially blogged about here), Wanda Rutiewckz explains the mortality that she is seeped in after having over 30 of her closest […]

i like mountain climbing because it is a particulary challenging tasks.;

Current article produced by our very own blog page

http://www.foodsupplementcenter.com/benefits-of-ginger-root/