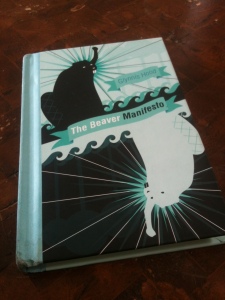

The Beaver Manifesto

eavers.

There, I said it.

Right on my minimalist-themed blog. Beavers.

Beavers have personality. They are resilient, stubborn as anything, and they look hilarious. People also just even think the word is hilarious…But did you know their prehistoric counterparts (Castorides ohioensis) were three meters long and weighed between 60-100 kilograms (roughly as much as a black bear)? There were also prehistoric versions that weighed less than a Chihuahua, tipping the scales at a scant 1.5 kilograms.

Neat to know? Sure. Relevant…maybe? In a little more than an hour I learned all this and more, thanks to Dr. Glynnis Hood’s The Beaver Manifesto.

This book is about beavers. Kind of a strange topic for a quick little chat book, but crazier things have gotten way longer books published–heck, even documentaries shot. Dr. Hood, former Parks Canada warden is beaver-obsessed. She wrote her entire doctorate on beavers, and currently has three beaver lodges as her closest neighbours. She is an incredibly kind author. Doubtlessly aware of the obscurity and perhaps the inaccessibility of her work, this short, novella-style essay is published in an incredibly easy to read, slightly-larger than hand-sized, elegant hardcover, and cuts straight to the core of what beavers are all about. Dr. Hood’s fully actualized as an author, shyly mentioning international beaver conferences and including such tidbits as:

Being friends with someone who has studied beavers for so long has definitely increased [my friend’s] success when playing the Canadian version of Trivial Pursuit.

Her enthusiasm for the little rodents is fully contagious, and by the end of the book I was completely taken by the little beasts.

She opens by describing the anatomical evolution of the species, summarizing that

…in the end the beaver evolved to what we see today: a semi-aquatic mammal with a bent towards environmental engineering.

In this way Dr. Hood is also able to make important ties between the beaver and ecosystem resiliency. For example, during periods of drought, beavers are actually able to mitigate the drought’s impact on the ecosystem by controlling the levels of water bodies, ponds and streams through the construction of troughs and burrowing around root structures to divert and increase the amount of available water.

She then looks at the human relationship with beavers, and the impact of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) as a corporate entity in the colonizing of Canada. Catalyzed by the surge in popularity of beaver pelts in Europe, the HBC’s voracious burnt-earth policy quickly swept Westward across the Canadian prairies in search of more. Beavers are non-migratory and easy to spot (thanks to their elaborate lodges and distinctive landscaping handiwork), making them easy pickings for the trappists of the day. As beavers verged on extinction, cultural values suddenly lurched left: national parks began to emerge, nature began to become valued as an entity unto itself, and beavers (among other species) began to be (quite successfully and controversially) re-introduced in many of the areas they had previously been hunted to extinction, like Elk Island National Park (Alberta).

Dr. Hood ends her quick tale by citing that the more that people know and understand the complexity of ecosystems, the more likely they are to make decisions that will positively (or at least less-negatively) impact the environment. Beavers mitigate the effects of drought, therefore can be an important indicator of ecosystem resiliency. Dr. Hood’s quick book takes you in, quickly, directly informs of the facts, her central argument and sends you out on your way, making it well worth the quick read. It certainly left me with things to ponder.

In closing, Dr. Hood touches upon beavers as integral to the Canadian identity. She points out that beavers appeared on our first stamps, our first military uniforms and became our official emblem (although not until 1985). She touts that Canada was built on the back of the beaver, and quite succinctly that:

In many ways Canada is a country with a split personality, one that defines itself by the very wilderness it nearly destroyed.

I loved this message of the book. I’ve always really appreciated having the beaver as our national emblem. This article that was published by the Globe and Mail in October (2011), angered me to no end. In a nutshell, the article summarizes a Conservative Senator suggesting that the beaver emblem is a little dated, and why not replace beavers with something more noble, like the polar bear.

I am fully aware that my initial understanding of why beavers were chosen as our national emblem was highly white-washed and surface, but I understood that the beaver was chosen for it’s hard work, it’s universality across Canada, it’s ability to engineer and adapt. I liked it because it appealed to my immigrant and factory/farmer roots: if you work hard and persevere, success can be yours. I liked that it was a rodent, and I loved that it was mutt-y looking crossbreed of a bunch of different animals.

Reading this little chat book I further appreciated the tremendous historical importance of the beaver, and Canada’s dualistic relationship with nature. The idea that the humble little hardworking beaver would be replaced by a top-of-the-food-chain, rare and quickly disappearing massive white carnivore, although incredibly appropriate, angered me to no end. I suppose only time will tell. I’m looking forward to reading the rest of the Rocky Mountain Books in this series.

Polar bear, Pond Inlet, November, 2011 c/o fellow Parks Canada staff Rob Campbell

Polar bear, Pond Inlet, November, 2011 c/o fellow Parks Canada staff Rob Campbell